Our April 18 sale of Classic & Contemporary Photographs features several of Dorothea Lange‘s iconic photographs from her time documenting for the Farm Security Administration, as well as her travels throughout Asia.

Deborah Rogal, Associate Director of Photographs at Swann, provides insight to the photographer and her practice.

Dorothea Lange

Lange began her career as the principal of a portrait studio, photographing San Francisco’s elite families. Her aesthetic awareness of design, composition, and the subtleties of light, the agent of photography, was matched by a keen sensitivity to the human condition. An ambitious young woman, Lange’s immediate social circle included Imogen Cunningham, Anne Brigman, and Consuelo Kanaga. Cunningham’s accomplishments as a young chemist working with Edward Curtis, Brigman’s association with Alfred Stieglitz, and Kanaga’s focus on political engagement helped to shape Lange’s distinctive personality, which friends had characterized as “charismatic.”

At the outset of her

“While there is perhaps a province in which the photograph can tell us nothing more than what we see with our own eyes, there is another in which it proves to us how little our eyes permit us to see.”

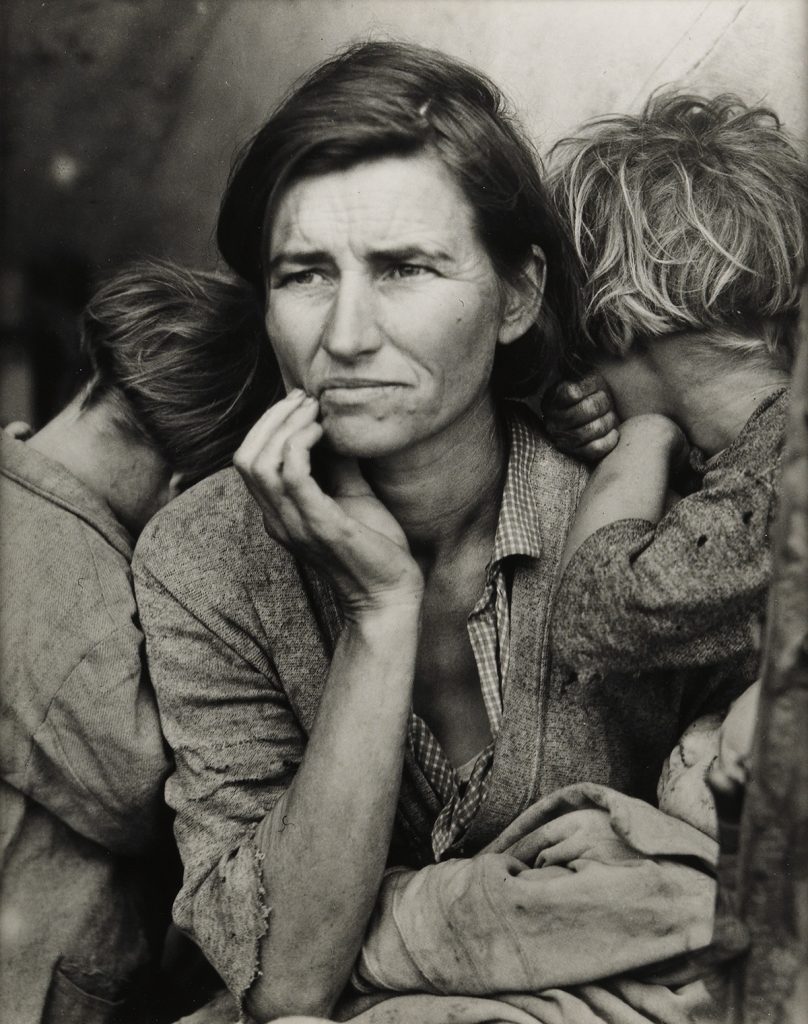

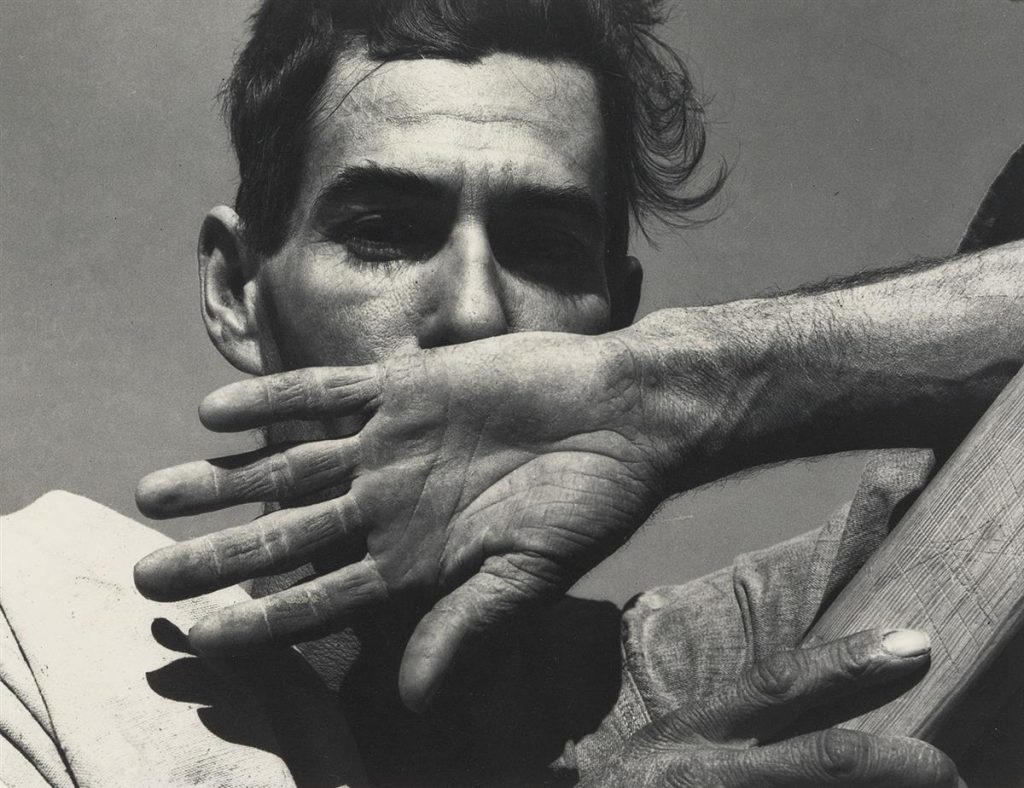

Eventually, Lange’s natural affinity to connect with people led her to transition from commercial portraiture to documentary photography. Her earliest images were shot near her studio and included the famous White Angel Breadline, 1933. Subsequently, she traveled for the Farm Security Administration and shot one of the greatest pictures of the twentieth century, Migrant Mother, 1936, a study of Florence Owens Thompson with her young children at pea-pickers migrant camp.

Photography as a Tool for Social Change

Lange fervently believed in photography as a tool for social change. After an early marriage to the painter Maynard Dixon, whom she divorced in 1935, Lange married the progressive agricultural economist Paul Schuster Taylor. They formed a professional partnership that lasted until her death. As a writer-photographer team, they collaborated on a popular publication about migrant workers during the Dust Bowl

In 1941 Lange received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the first woman awarded the honor. Shortly after, when Japanese-Americans were involuntarily transferred to Manzanar, an internment camp in California, Taylor

Travels in Asia

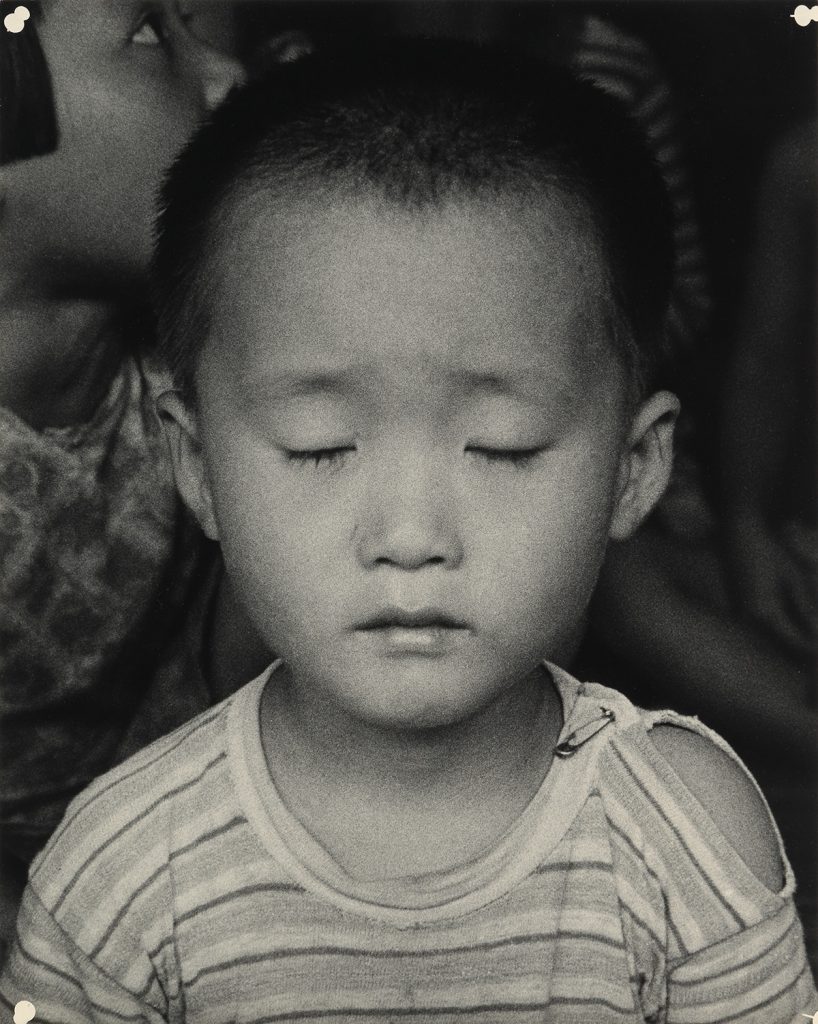

Lange had survived childhood polio and had difficulty walking. In the 1950s, as her health deteriorated, Taylor was offered a new position at the U.S. State Department that presented an opportunity to travel to Asia. Taylor, the academic-cum-activist, had long sought to effect democratic land reform in countries throughout the globe. Although Lange understood that her role was largely that of a diplomat’s wife, she purchased a 35mm camera in anticipation of the journey, planning to photograph throughout the trip. In 1958 the couple traveled extensively for eight months, visiting twelve countries.

Despite the poverty and

This consummate humanist portrait, made without the benefit of a telephoto lens, reveals Lange’s mature vision. Her approach pays homage to Lewis Hine, who was another early aesthetic influence. Like Lange in the 1930s-40s, Hine employed a Graflex camera during the years he documented child workers. Due to its technical limitations, he also shot group portraits with a focus on a single child, who was later highlighted in white gouache or cut-out and placed in montages.

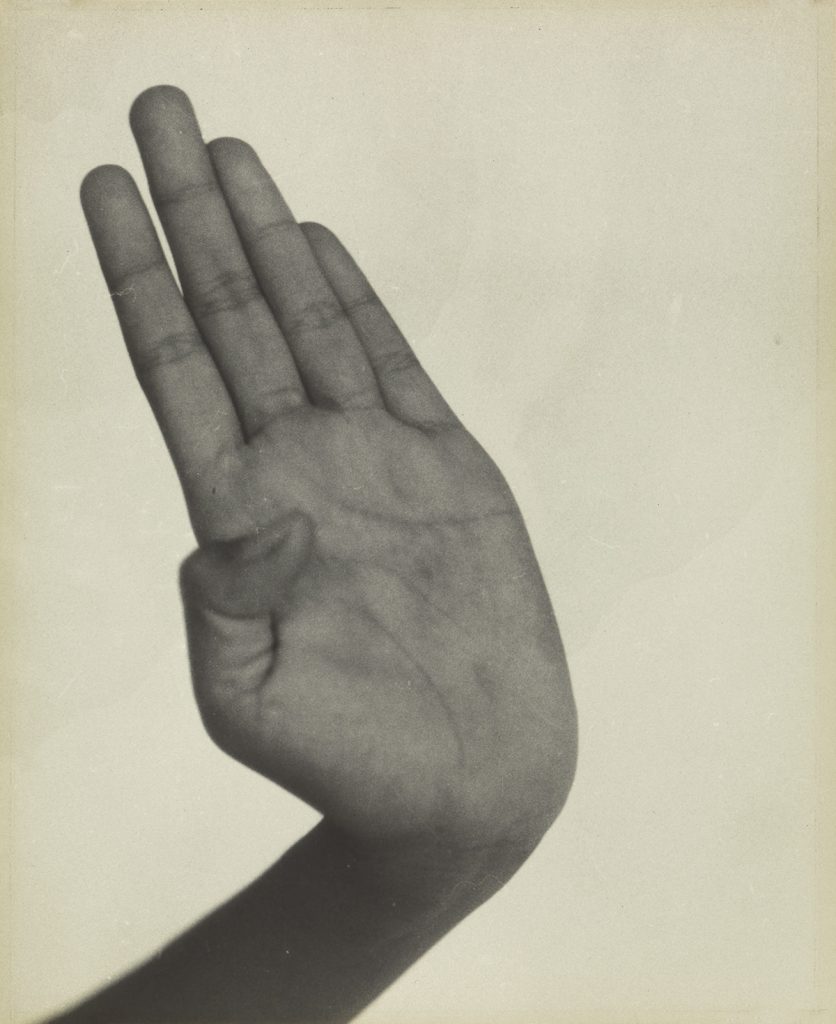

Korean Child was recognized as a masterwork by John Szarkowksi, curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, who was responsible for Lange’s retrospective in 1966. Szarkowski featured the image on the front cover of the exhibition catalog, and the rear cover was Hand, Indonesian Dancer, Java.

For more in our April 18 sale, browse the full catalogue, or download the Swann Galleries App.

The post Notes from the Catalogue: Dorothea Lange appeared first on Swann Galleries News.