Part I

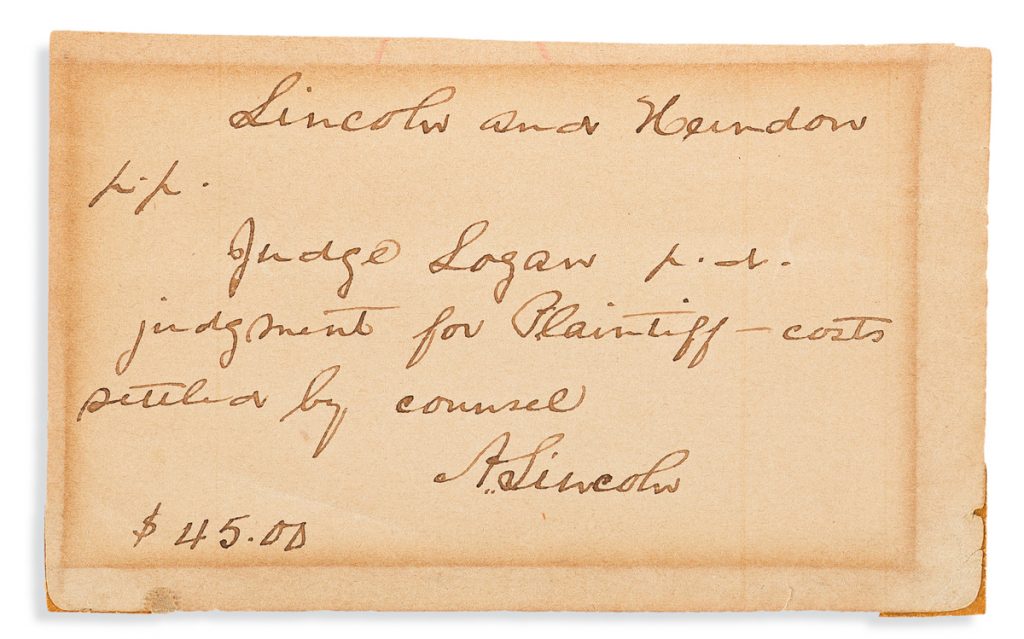

The authenticity of an autograph is a critical aspect of its value. A letter signed by an authorized secretary or signing machine in the name of a U.S. president, for instance, is invariably valued less than a similar letter signed by the president herself. Analogously, an inscription that has been forged is usually valued even less than a similar one created by an authorized secretary. But not always. Sometimes, the dramatic story behind a forgery, or the striking personality or skill of a forger, generates sufficient fascination to endow even forgeries with value. An uncommonly skilled twentieth-century forger of presidential autographs who used the alias “Joseph Cosey,” for example, produced forgeries that have become collectible (see Swann 2551, lot 67).

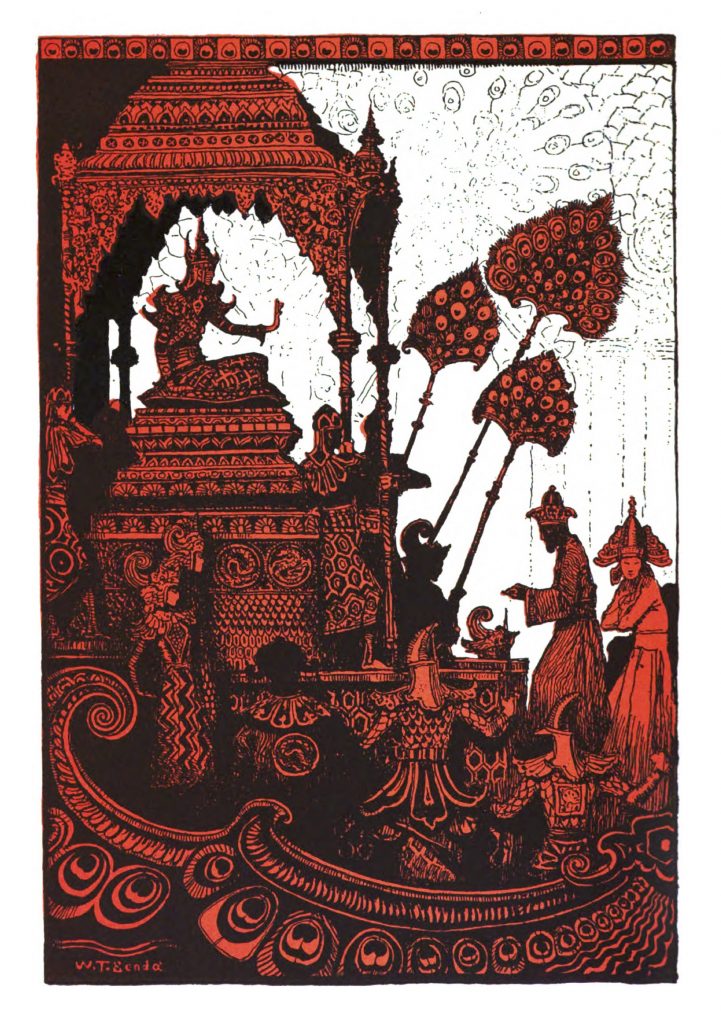

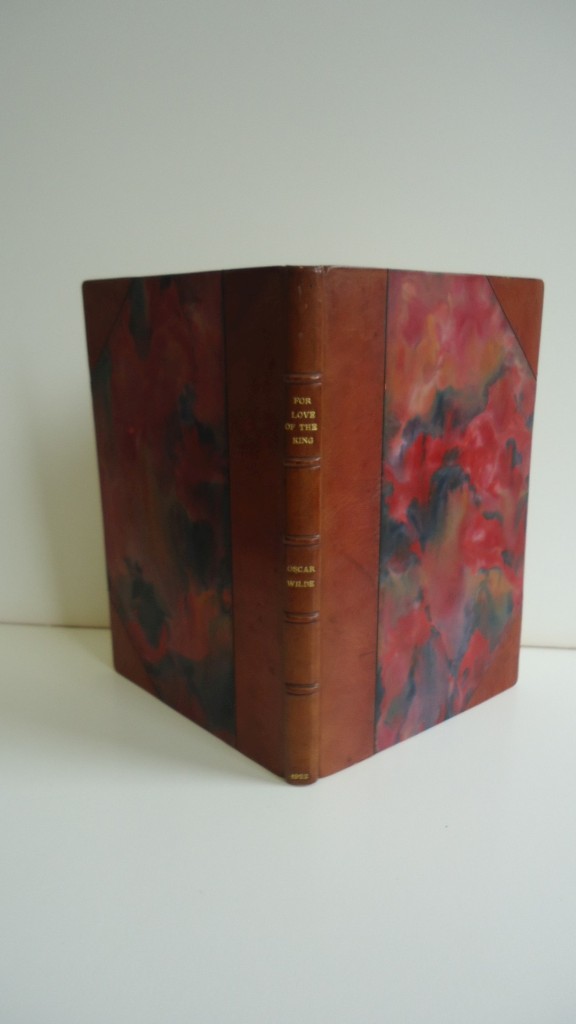

Authenticity in the domain of literature plays essentially the same role as it does in autographs, so it should not be surprising to find collectible literary forgeries as well. One of the zanier examples is that of For Love of the King: A Burmese Masque—a sort of fairy tale allegedly by Oscar Wilde, but actually written by a woman, known by many names, but usually referred to as Mrs. Chan-Toon (see Swann 2355, lot 275). Chan-Toon managed to persuade a major British publisher and others that her typescript of the story was authentic; the cunning employed in achieving this, and the colorful and idiosyncratic life she led, contribute to the reasons collectors still find value in the book published from her typescript. Although there was a court case involving the book, no court has ever ruled it a forgery. In what follows, we briefly explore the events and personalities surrounding For Love of the King, and the evidence demonstrating that the story was not written by Oscar Wilde.

Mrs. Chan-Toon

Mrs. Chan-Toon, born Mary Mabel Cosgrove on May 12, 1873, in Cork, Ireland, had a number of things in common with Oscar Wilde: she was drawn to read and write literature at a young age, she lived life as if it were itself an artwork, she lived with a grave secret, and she endured misery and poverty upon the revelation of that secret. Wilde’s secret, of course, was his sexuality, the public discovery of which resulted in his imprisonment and later exile in Paris. Chan-Toon’s secret (after her first marriage) was the whole of her identity, which as soon as it was partly revealed, she hid again by moving to a new place and assuming a new name—once in Scotland, again in Mexico, and again in Paris—preventing her from making a place in society. Her names changed twice by marriage, the first in 1893 when she became the bride of U Chan-Toon, a Burmese barrister at Rangoon (present-day Yangon, Myanmar), who died of heart failure 11 years later; the second in 1911 when she wed Armine Wodehouse Pearse, who died 7 years later in the first World War.

She was also known to have presented herself on various occasions as “Princess Chantoon,” “Princess Araken,” “Princess Orloff,” and before becoming Mrs. Chan-Toon, she employed the literary pseudonym, “Mimosa.” In the 1920s, when she began peddling For Love of the King and other forgeries, Chan-Toon was occasionally seen in Paris and London wearing a black cloak, suitable for attending the opera, if it were not for the fact that the shoulder was soiled by the dung of her pet parrot who perched there. Co-Co, the green-plumaged parrot, remained in its place wherever Chan-Toon went, with the help of a string that connected a leg of the bird to one of Chan-Toon’s buttons.

Publishing For Love of the King

In October 1921, Mrs. Chan-Toon persuaded Hutchinson’s Magazine to publish For Love of the King, a “Remarkable Literary Discovery: New Unpublished Work by Oscar Wilde,” and two months later, The Century Magazine also accepted from her what it took to be Wilde’s story, publishing it as “A Burmese Masque in Three Acts & Nine Scenes: For Love of the King.” The remarks introducing the story in Hutchinson’s Magazine demonstrate how the editors were taken in: Chan-Toon claimed that her parents were close friends of Wilde’s parents, that she grew up with the Wilde family, nearly marrying Oscar’s brother Willie, instead settling down with a nephew of the King of Burma, Mr. Chan-Toon. The fact of the marriage could be confirmed, but the delicious details about the relationships between Mr. Chan-Toon and the King, and between the parents of Mrs. Chan-Toon and the Wildes, was not so readily established, partly because the relevant members of the Wilde family had been dead by the time Oscar passed away in 1900 and Mr. Chan-Toon died four years later.

What probably clinched the deal for Hutchinson’s was the letter that Mrs. Chan-Toon (or rather her agent, Henry Noble Hall) presented to them, which they reprinted in the introduction to the story, apparently written from Oscar Wilde to Mrs. Chan-Toon. In the letter, Wilde thanked her for the gift of her story entitled Told on the Pagoda (which it could be conformed was the title of a work by Mrs. Chan-Toon), described how Wilde had come to write For Love of the King after spending time with Mr. Chan-Toon, and stated that the typescript of the story was his gift to her. The letter, presumably bearing Wilde’s signature forged by Chan-Toon, was never released by Methuen. Chan-Toon’s clever weaving of truth and lies handily explained why a previously unknown work by Wilde made a sudden appearance after the author’s death.

Perhaps it did not require much to persuade Hutchinson’s Magazine of the authorship of For Love of the King, since the sensation that publishing it promised to produce was a powerful temptation to overlook the gaps in the evidence. Regardless of how lax their fact-checking, that Hutchinson’s published it engendered an aura of authenticity around the work, which was enhanced after The Century followed suit. Then, in 1922, Mrs. Chan-Toon (or her agent) approached Methuen & Company, the same publishers to whom Wilde’s literary executor, Robert Ross, had turned in order to issue in 1908 the First Collected Edition of the Works of Oscar Wilde. In October following Chan-Toon’s first contact, Methuen published For Love of the King as a supplement to the Collected Works.

The Methuen supplement had aroused the indignation of Christopher Millard, a London book and manuscript dealer who had worked with Ross and had published an extensive Wilde bibliography, since to him, there was no doubt that For Love of the King was a forgery. Millard went so far as to publish a screed against both the publisher and Chan-Toon, asserting that Methuen had swindled its customers by selling a forgery, and furthermore wrote to Wilde’s son, Vyvyan Holland, stating that “For Love of the King was not written by O[scar] W[ilde] (2) that the introductory letter . . . is a forgery and (3) that Ross never asked permission to include the play in the collected works.” In 1926, Methuen then sued Millard for libel, which Millard welcomed, believing it would provide an opportunity to prove that For Love of the King was a forgery. Chan-Toon was unavailable to testify in the trial, because she was serving a 6-month prison sentence for having stolen £240 from an elderly woman in London. Even if she had testified, it likely would have made no difference, since the legal details of the case did not depend upon the authenticity of the work Methuen published. In the end, the verdict went against Millard, who was sentenced to pay £100 in damages as well as court costs.

Part II: Coming Soon.

More from Marco Tomaschett

Consign with Swann.

The post For Love of the King: the Wild Story of a Forged Wilde Story appeared first on Swann Galleries News.