Whether a seasoned collector or a newbie to the world of original illustrations, you may have several questions about why things look as they do, which of them to fix, and which to leave alone. What constitutes as “character” to one person may be a visual distraction to another. Illustration Art department director Christine von der Linn talks a bit about those fun, often factually important marks and offers a few examples of when restoration might be warranted.

While most other works of art appearing at auction are finished, approved prints or canvases, original illustrations often have their “bones” showing. By this, I mean that one often encounters images that still contain labels and marks, usually on the front or back (recto or verso) margins that served as directions to the printers and publishers who would reproduce the work.

The above study for a cigarette advertisement by the famous Golden Age illustrator J. C. Leyendecker is a perfect example of how fascinating preparatory sketching, unfinished, and re-worked details become beautiful and appealing for display. They are a direct portal into the artist’s creative process. The master of sartorial detail whose ads for the “Arrow Collar Man” and illustrations of handsome, fashionably dressed men defined early-twentieth-century American style, Leyendecker sketched repeatedly so that the finished image would appear effortless. Just look at that cuff and the drape of those trousers! His finished canvases sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars and so these studies, smaller and more commonly available, become highly collectible and treasured for their “unfinished” look.

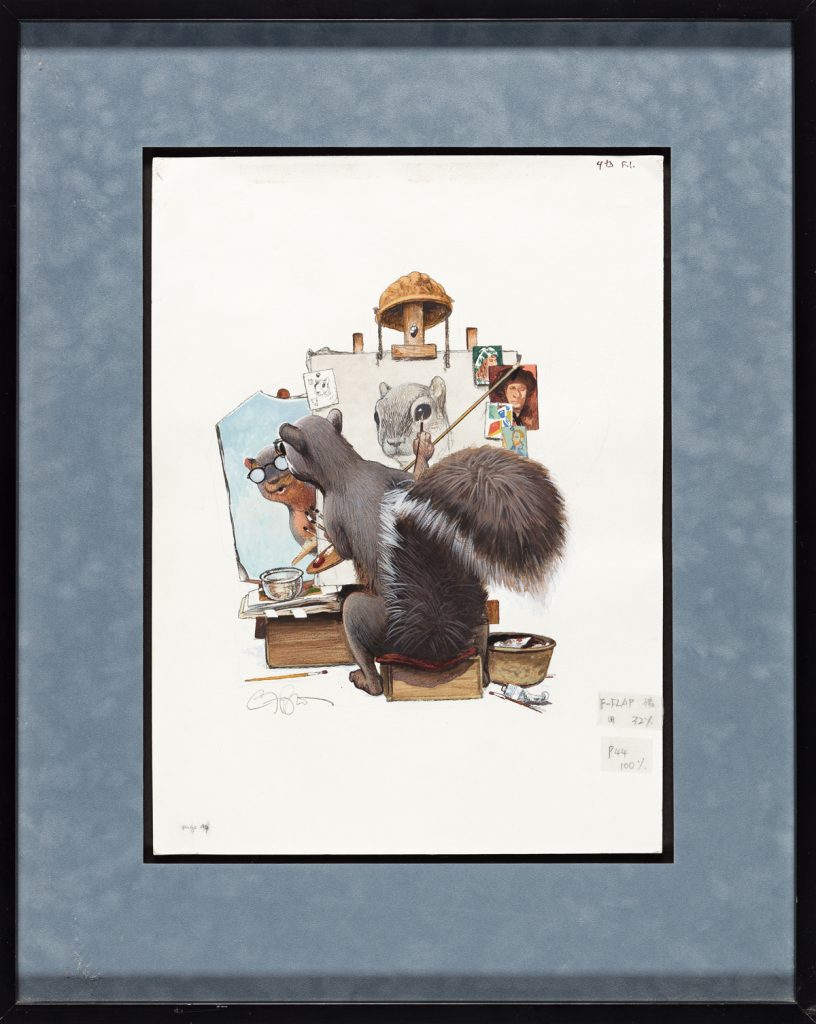

Other marks might include captions, notes to (or by) the printers including page numbers where the illustration would appear in the publication, and sometimes the artist’s or publisher’s stamps or labels indicating ownership, date and place of publication. These marks give the illustrations a look that is more raw than a finished piece and may offer enlightening details about the illustrator’s methodology. It is often a quality that is attractive to collectors who enjoy this visual history as part of a work’s display, often matting and framing to show those notes as in the cover lot of our June 2021 sale by C.F. Payne above.

While most other works of art appearing at auction are finished, approved prints or canvases, original illustrations often have their “bones” showing.

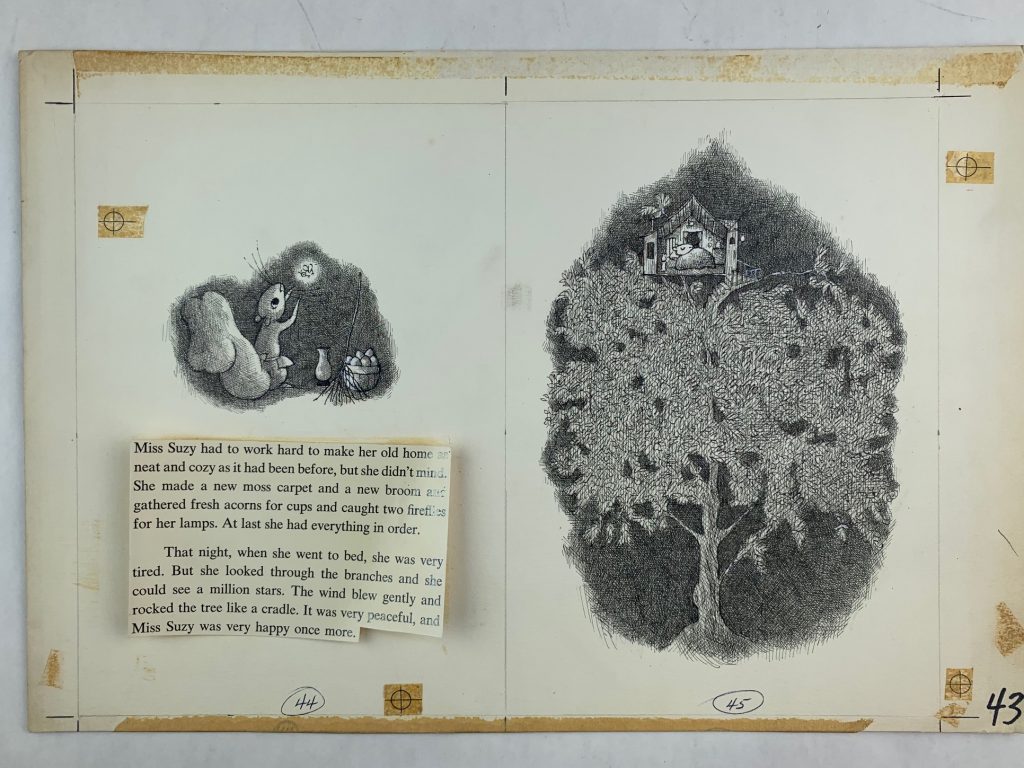

Crop marks (also called trim marks), common to published illustrations, are the thin lines placed at the corners of the paper or board on which the illustration was created, indicating where the finished project was to be trimmed. Registration marks are used to align the artwork with any other application during production, usually if wording or backgrounds were to be later applied to the final image. They often look like a small target with a cross and sometimes appear near the crop marks as in this illustration for the children’s book Miss Suzy by Arnold Lobel:

This group of story boards, single and double-page spreads contained registration marks, page notations, and scattered printing notes in the margins, showing how the book was put together; the text overlays were printed and pasted on (like most mock-ups, the old adhesive did not hold terribly well).

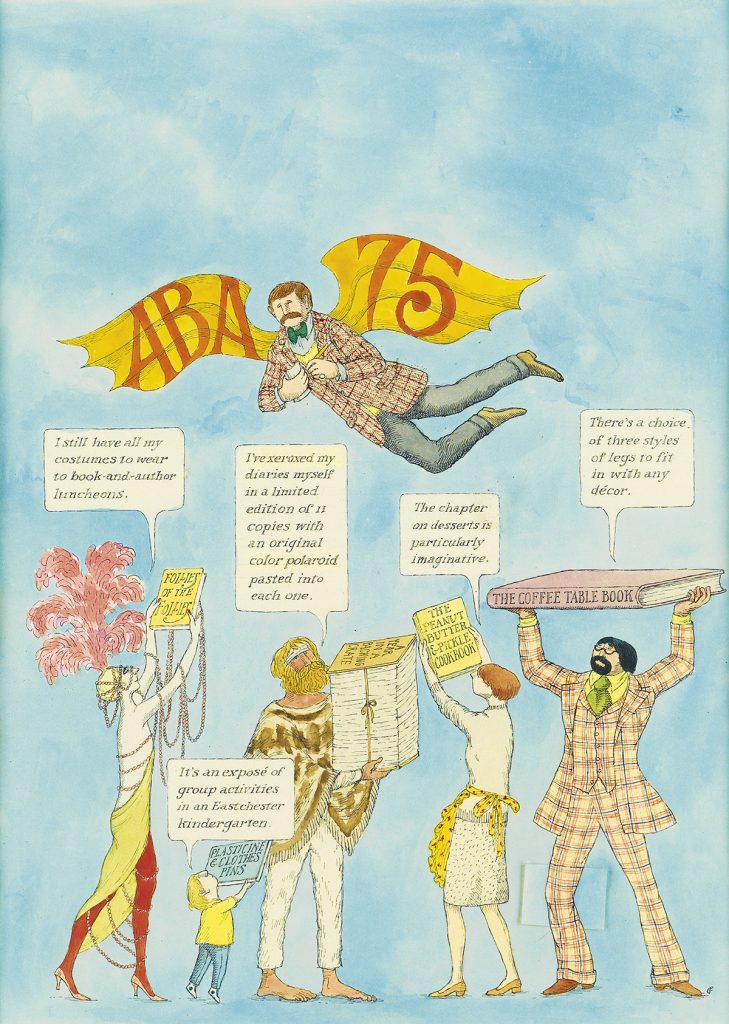

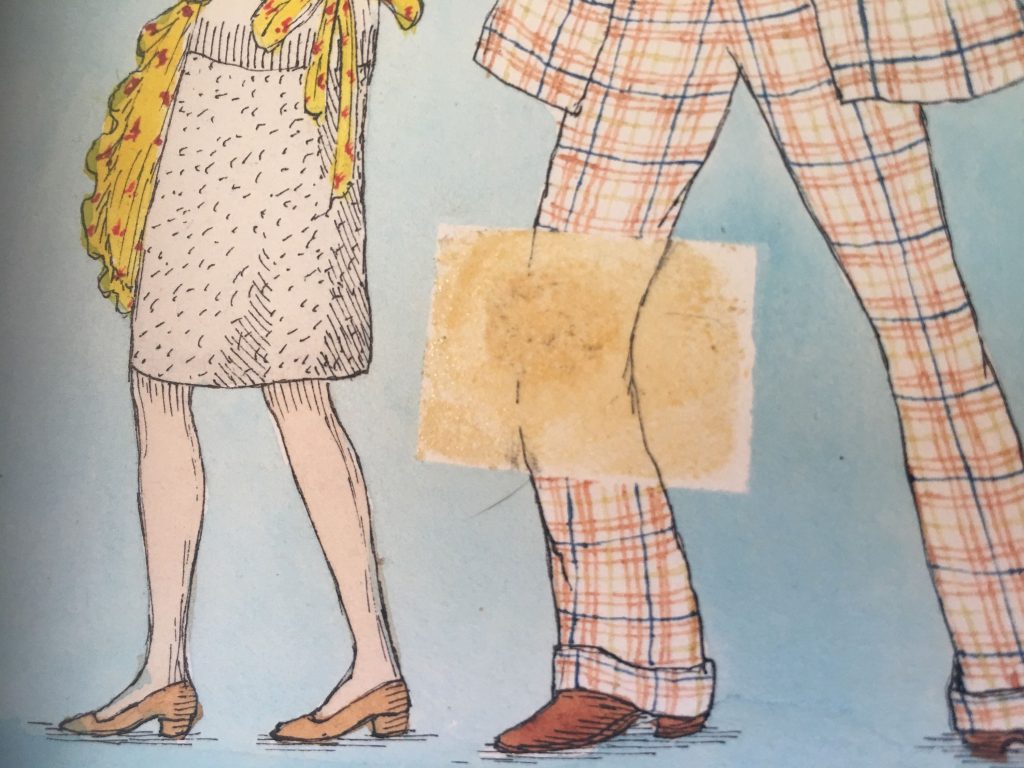

Sometimes, in addition to the registration marks, reworked portions of a drawing were collaged over the original. In other cases, celluloid or clear acetate overlays were applied on top of the work and allowed for notes or other features pertaining to the final drawing. Here are two good examples of both in works by Edward Gorey. In the first, you can see a patch applied to the plaid trousers of the man on the far right. Beneath the flap was an originally inked and anatomically awkward kneecap that Gorey could not accept.

The second drawing, used for the cover of Playbill, contains the printer’s specific notes, and shows the progression from original drawing to finished product.

Turning to physical aspects that are not necessarily welcome, there are certainly some rights and wrongs of restoration. Both consignors and buyers consult with us about when and how to approach restoration and/or conservation. At Swann, we work with both paper and canvas restorers who understand what we are trying to achieve and are considerate of our deadline-driven business. Cost is a consideration as well, but you should keep in mind that there are several smaller, helpful remedies that can be applied to preserve and present your illustration artwork.

Whether the work in question is an affordable cartoon or an expensive fine art canvas, you want to care for it properly. The most common concerns that restorers hear is if a spot, tear, or other issue will become worse and hurt the artwork, if is it safe to remove, and how should they preserve the work. Just like your favorite tailor can alter a terrific garment you almost put back because it does not fit, a trusted restorer can give you the confidence to go after a work of art or illustration you may be hesitant to buy because of a condition issue. A discussion with the specialist can be immensely helpful in determining what is the best approach and do not feel shy about asking a conservator for their opinion and a quote.

Among major concerns and the most common treatment is cleaning. A canvas surface exposed to the air can collect dirt, grease, or smoke over time, diminishing the painting’s beauty and detail. Such was the case with this pretty little Harry Anderson painting of a woman reclining in the snow which, at first, looked more like muddy March slush and suffered a small puncture to the surface. With the consignor’s permission, we received a quote from a professional restorer which proved to be worth the small investment. After a cleaning and repair, the work revealed a brightness, detail, and resembled the fresh woodland snow that Anderson originally painted.

Before Restoration:

After:

The final two examples are works by highly collectible American artist and illustrator Rockwell Kent. His works, ranging from hundreds of magazine and book illustrations to large, fine art canvases, were handled by numerous publishers, galleries, museums, and collectors.

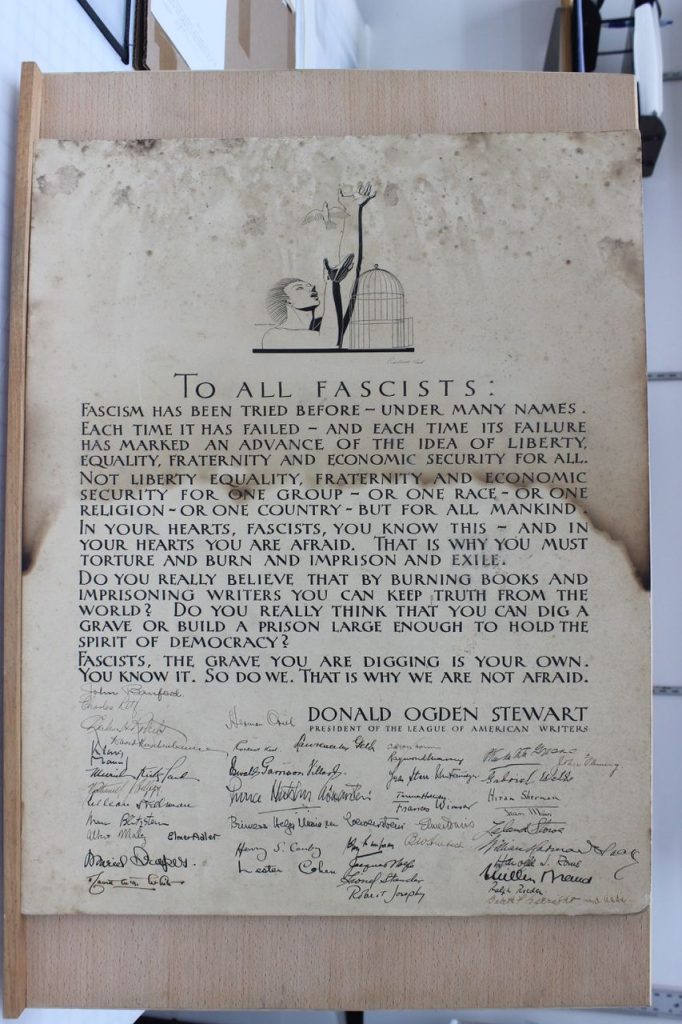

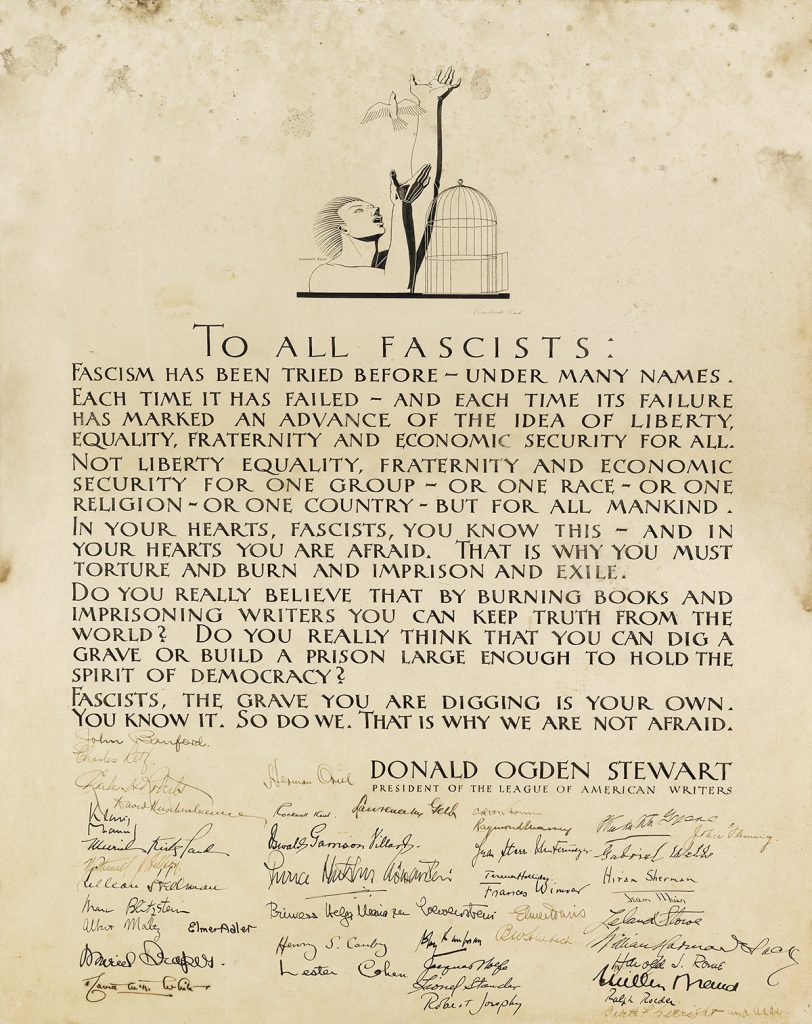

The first is a unique anti-fascism broadside for The League of American Writers, written by Donald Ogden Stewart with headpiece illustration by Kent and signed three times by him, circa 1937 or 1938. Neglected in Stewart’s attic for decades after his death before its rescue by family members, it was terribly stained and mildewed. Since it was India ink on paper mounted to board, we consulted our paper conservator who applied a safe chemical bath to it to lessen the staining, preserve the ink, and prevent further deterioration.

Before Restoration:

After:

The dramatic difference is evident. This was a more expensive but very necessary conservation and one that paid for itself when the important work achieved $6,500 at auction to its $3,000-$4,000 estimate.

Matting and framing present another wide range of poor archival decisions. We have seen artworks glued down to mounting boards, mattes adhered over important stamps and printing information, even the artist’s own captions and signatures. We approach each framed consignment with a certain amount of trepidation.

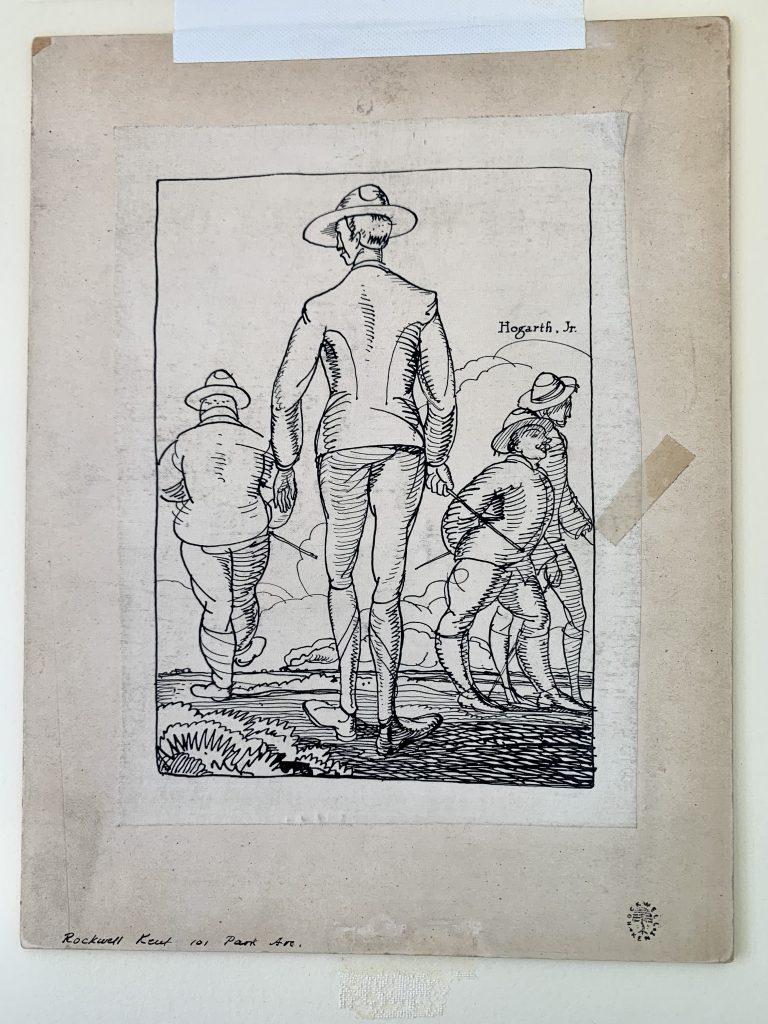

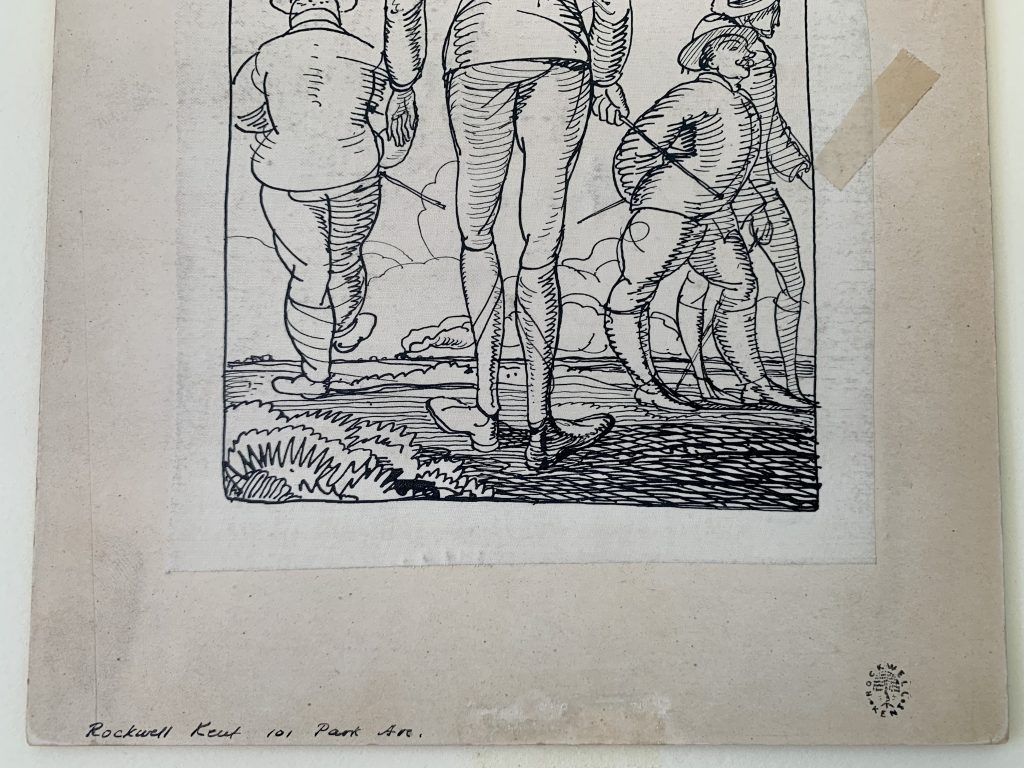

This second Kent example was a victim of this. The small drawing was framed to cover Kent’s handwritten signature and address on the bottom left of the original board and his estate stamp on the right, both crucial elements in terms of provenance, aesthetics, and value. But worse, the insensitive decision to secure the board to a window matte for framing was performed with bright white hinging tape above and below the image, right in between the signature and stamp. We knew it would not show well in the sale catalogue for potential bidders and so this under-$200 fix turned it from unsightly to presentable.

Before Restoration:

After:

Illustration Art instills delight and evokes fond memories. Our interest in this fascinating genre is enhanced when we consider the physical evidence of editorial choices through annotations and markings. And when proper care, display, and presentation are applied, you can preserve and enjoy them for many years.

For more examples of original illustration art with artist and editor markings, look at some of our previous catalogues, and keep an eye out for more details on our upcoming sales in 2021.

More from Christine von der Linn:

The Rise of Illustration Art in the Public Eye

The post Let’s Get Physical: Telltale Marks and Restoration Tips for Illustration Art Collectors appeared first on Swann Galleries News.