The Whitney Museum of American Art’s recent exhibition, Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945, was a comprehensive evaluation of post-revolution art in Mexico and the powerful influence it had on artists of America. The exhibition was curated by Barbara Haskell, and assistant curator, Marcela Guerrero, and ran from February 17, 2020, to January 31, 2021.

Below we reflect on the Mexican muralists who influenced the artists involved in the Works Progress Administration programs, as well as many additional Modern artists that followed after them.

Los Tres Grandes

In 1920, after a decade of revolution and unstable factions seizing control of the Mexican government, Álvero Obregón was elected president. Under Obregón’s leadership, and with the aid of José Vasconcelos, his Minister of education, they launched a program to build schools and employed artists to decorate the walls with murals in order to tell the history of the Mexican peoples in imagery.

From this program, three leading talents emerged, often referred to as Los Tres Grandes: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Their murals—and most paintings, film, and photography of their contemporaries—celebrated the indigenous peoples of Mexico and promoted Socialist government beliefs shared by many artists active in Mexico at that time. These artists’ influence on American art was profound, as can be seen in works by over forty Americans included in the exhibition, and many of these Americans who drew inspiration from the Mexican Muralists would end up contributing to the WPA’s artist programs.

Related Reading: The Artists of the WPA: The Promise of a New Deal

Projects in the United States

José Clemente Orozco

Clik here to view.

Image courtesy of Benton Museum of Art Pomona College

At the end of Obregón’s four-year term as president, the funding for mural projects declined, with most awards going to Diego Rivera. Los Tres Grandes sought mural projects in the United States, beginning with Orozco, who completed the first modern mural in America, Prometheus, at Pomona College, Claremont, CA, in 1930.

Orozco arrived in the United States in 1927 and in March 1930 was commissioned by Pomona College in part due to the efforts of José Pijoán, a professor of Spanish civilization there and Sumner Spaulding, architect of the recently dedicated Frary Hall.

Clik here to view.

The theme of Prometheus bringing the fire of knowledge to humankind was chosen, both because it was fitting for a college hall, and because Orozco had his own internalized interpretation of the story: personal artistic sacrifice to benefit the masses. Orozco clearly identified with his mythical subject, placing great emphasis on Prometheus’ large hands in both the mural and the present painting. Orozco’s oeuvre is replete with prominent hands, perhaps owing to Orozco having had his own left hand amputated after an accident involving fireworks as a young man. Orozco would have been well acquainted with the Prometheus myth having studied classical casts as a young artist and from his association with Alma Reed and Eva Sikelianos in New York, and their 1929 intention of staging Prometheus Bound.

In the Pomona College mural, Orozco highlighted two subjects of the painting of great importance: the colossal Titan Prometheus reaching for the fire and the dynamic crowd. Some in the crowd are delighted and embrace; others scorn Prometheus’ gift, reflecting the mixed reception of Orozco’s art. Though there was conservative opposition to Orozco’s mural, Orozco was also highly praised. By May 1930, he had already been commissioned to paint murals at the New School for Social Research in New York. The Pomona College mural, which predated Diego Rivera’s arrival in San Francisco, heralded in a new era in mural painting. According to David W. Scott in “Orozco’s Prometheus,” appearing in College Art Journal in Autumn 1957, “Prometheus stands as a masterful introduction to what was to become the most astonishing cycle of cosmic myths created by a modern artist.”

Jackson Pollock traveled to California to see the mural and was so inspired that he kept an image of Prometheus in his studio. Mitchell Siporin and Edward Millman studied the murals of Orozco before starting their frescos for the St. Louis Post Office, the largest mural project of the WPA.

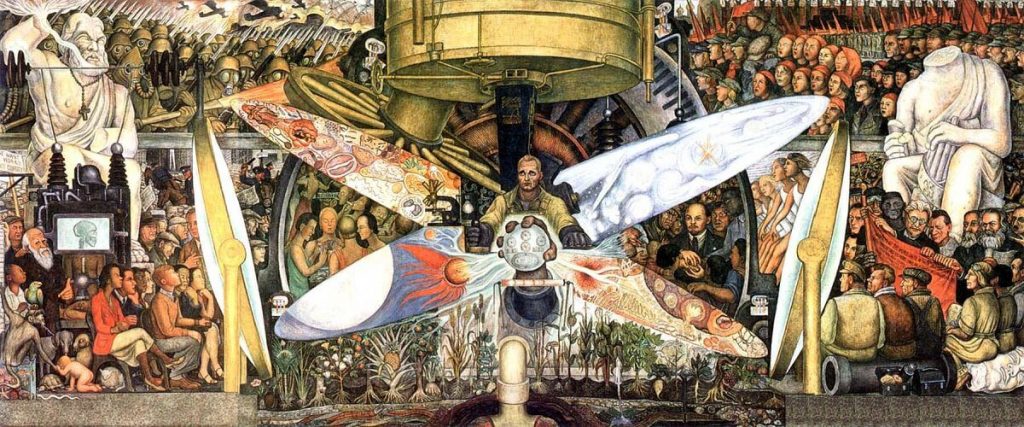

Diego Rivera

Clik here to view.

Image courtesy of diegorivera.org

Diego Rivera created murals in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City. His Man at the Crossroads, a fresco commissioned by the Rockefeller family for Rockefeller Center, was destroyed after Rivera refused to modify the mural by removing the image of Vladimir Lenin from the composition. Rivera would later recreate the mural in Mexico City. Not only did he influence American artists indirectly through his artwork and activism, but he also taught several artists that would go on to use their learned fresco craft under the employ of the WPA.

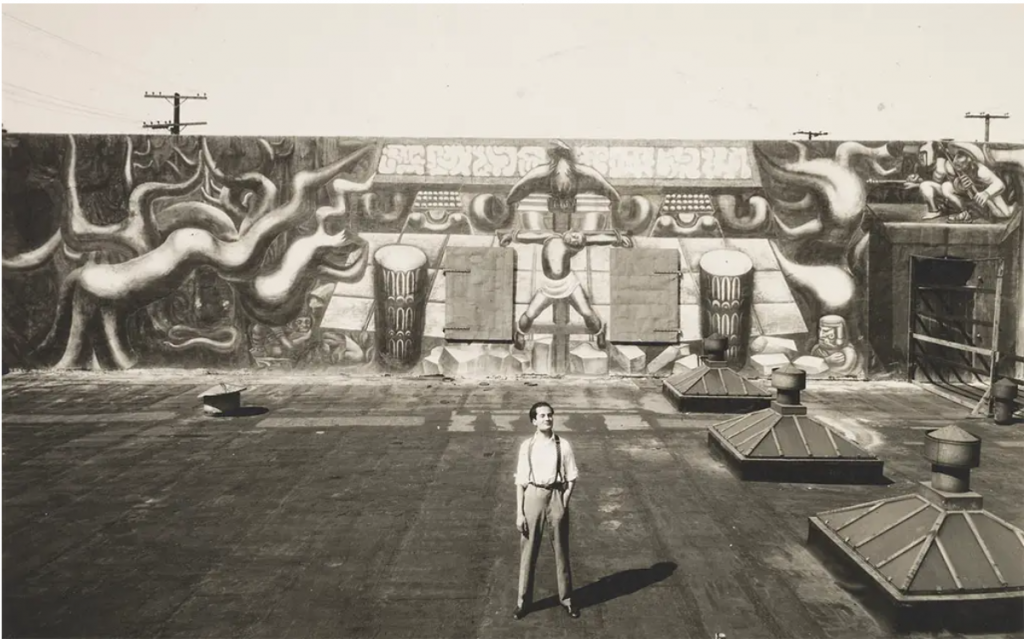

David Alfaro Siquieros

Clik here to view.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, the most progressive of the three, would only complete one mural in America. América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos was completed in Los Angeles in 1932. The imagery, with a bound and murdered indigenous person at its center, proved too much for American audiences and was soon painted over. In 2012 the work was presented to the public after an extensive restoration and renovation funded by the Getty Foundation. Siqueiros’ use of industrial-grade paints and materials influenced Jackson Pollock who studied under Siqueiros in his Experimental Workshop, which he opened in New York City in 1936.

The parallels of the art created in Mexico under the Obregon presidency and that of artists working in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, WPA programs is extraordinary. Expressing hope through the imagery of hardship—is an American tradition in our art, theater, and our music.

Related Reading: Etched in History: Printmakers of the Federal Art Project

The post Mexican Muralists & Their Impact on the WPA appeared first on Swann Galleries News.